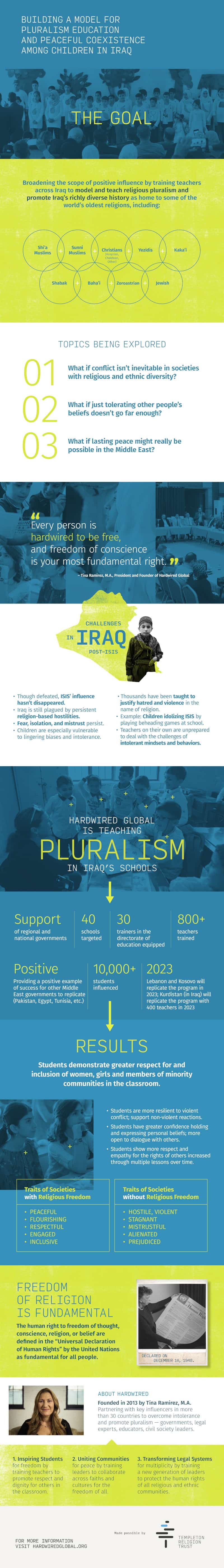

What if conflict isn’t inevitable in societies with religious and ethnic diversity?

What if just tolerating other people’s beliefs doesn’t go far enough?

What if lasting peace might really be possible in the Middle East?

The end of fighting rarely means a clean break from the conflicts that caused it. But with positive intervention, those conflicts can be diminished and healed over time.

That kind of reversal is happening in portions of Iraq, reports Tina Ramirez, M.A., president and founder of Hardwired Global. As a powerful example, she tells the story of a school director named Zyad in Mosul, a major city in northern Iraq. When the Islamic State took over the region and wanted to impose its radical ideology on classroom curricula, he closed the school rather than give in to their demands.

Mosul was liberated in 2017 after years of ISIS violence, but Zyad believed the damage done to his city – both physical and psychological – made it beyond repair. He had no plan for reopening the school. Until one small girl changed his mind. When Zyad saw her, dutifully carrying her backpack and dressed in her uniform, walking through the rubble toward school, he realized he had no choice but to reopen. Clearly, education was vital to her, to students like her and, therefore, to the future of his city as a whole.

Yet, by reopening, he put himself and his teachers on the frontlines of combating the fear and mistrust still rampant in this post-conflict society. On their own, he knew they weren’t equipped to deal with what they were facing.

Zyad turned to Hardwired Global, founded by Tina Ramirez, for the resources he and his teachers needed to start to rebuild a culture of respect and cohesion – initially within their school, and extending outward from there to touch the hearts and minds of parents and the community.

Zyad is confident the effort that began in his school is now successfully helping to rebuild Mosul with a culture of respect and cohesion.

Hardwired was founded in 2013 on the belief that people’s differences – in opinion, thought, belief and expression – can be vibrant points for discussion rather than flashpoints of conflict. The organization has worked with governments, legal experts, educators and civil society leaders in more than 30 countries to advance legal and social protections for the human right to freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief – freedoms defined in 1948 by the United Nations as fundamental for all people.

“Every person is hardwired to be free, and freedom of conscience is your most fundamental right,” emphasizes Ramirez.

However, in too many parts of the world, many are unable to exercise this deep-seated freedom. The result is a climate of intolerance, fear, hostility and division that easily fuels violence and wars. And those negative attitudes usually remain smoldering long after the fighting has stopped.

Mistrust and fear persist in post-conflict societies among neighbors who have been targeted for their religious and ethnic differences, particularly those who were forced to flee their homes for safety. And children who grew up in such environments are especially vulnerable to adopting and perpetuating these attitudes and behaviors, Ramirez reports.

Often called “the cradle of civilization” and home to some of the world’s oldest religions –Shi’a Muslims, Sunni Muslims, Christians, Yezidis, plus other minority communities – post-ISIS Iraq is still plagued by lingering conflicts that threaten its rich pluralistic heritage.

“Children living under ISIS were influenced by the group’s extreme intolerance toward anyone who disagreed with them,” Ramirez notes. “And many children, even in areas outside of the group’s control, have been influenced by the examples of intolerance they’ve witnessed. It’s in this context that thousands of children were taught to justify violence against others in the name of religion, or to justify violence in retribution for the attacks against them.” Just one example: she reports that some students have idolized ISIS by playing beheading games at school for fun.

With funding from Templeton Religion Trust, Hardwired was able to advance a pilot project in 2019 in Mosul and the Nineveh Plains that focused on education. Its approach was to ready “master trainers” who could then help teachers develop new ways to promote pluralism and human rights in their classrooms. Their methods focused on addressing the underlying root causes of conflict – the misconceptions, biases and fears that exist within communities towards one another.

Building on the success of the pilot, the organization has now been awarded additional funding to significantly expand its efforts.

As a “top-down” and “bottom-up” approach, the project focuses on earning buy-in from regional and national governments. At the same time, it works at the community level by equipping primary and secondary school teachers to respond to their everyday issues and challenges.

“Peacekeeping efforts need to go beyond tolerance,” explains Ramirez. “True reconciliation and peaceful coexistence require pluralism: active engagement with each other across our deepest differences. With pluralism, different opinions and ideas become points for rich discussion rather than flashpoints for conflict. Because conflict never begins with things we agree on.”

By training an estimated 400 – 600 teachers across 40 schools to model pluralism and promote Iraq’s rich pluralistic heritage, it has the potential to positively influence 8,000 – 12,000 Iraqi students. It’s also a significant opportunity to present proof of impact to other governments in the Middle East such as Pakistan, Egypt and Tunisia that are struggling with intolerance and deep divisions along religious and ethnic lines, thereby creating a broadening scope of positive influence and showing the world that conflict isn’t inevitable.

“Change may be possible even in the most challenging societies that exist today,” Ramirez says.

So far, the work of Hardwired is proving that progress is achievable, sometimes at a remarkably swift pace. As one student in Mosul expresses what he has learned, “Just because we believe different things, it doesn’t mean we are enemies.”

It’s a simple statement of an enormous truth — a certainty that, when put into daily practice, has the potential to be world-changing.