What if words are a gateway to understanding our brains? What if having a shared language could help us comprehend the human impacts of art? What if religions could rely on science to create places that kindle spiritual experiences?

On the one hand, viewing art — like viewing anything else — can be understood as straight-up biology. Visual inputs are received by nerve cells in the retina and travel from there to the brain’s occipital lobe in the back of the head where they get processed. It’s there, however, in the neurological and psychological theater of the human brain that the experience of art becomes incredibly complex – sometimes so mysterious, powerful and extraordinary that we struggle for words to describe it.

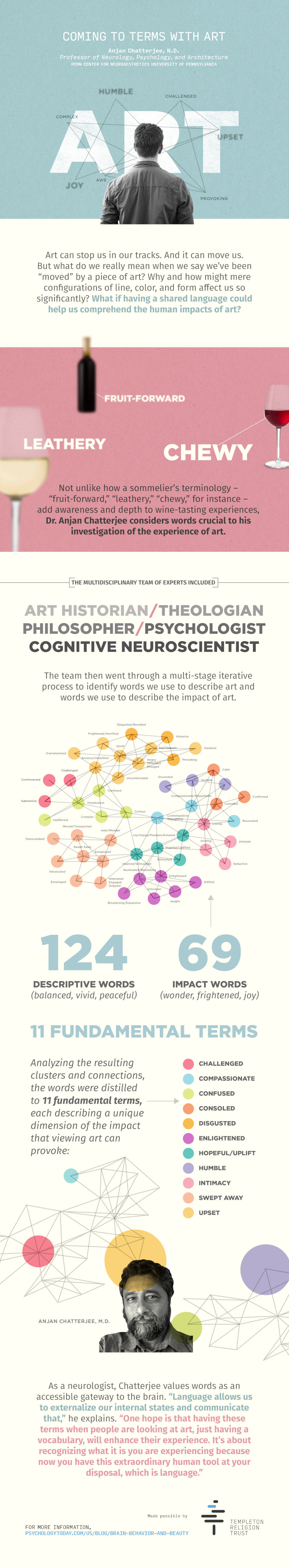

Art can stop us in our tracks. And it can move us. But what do we really mean when we say we’ve been “moved” by a piece of art? Why and how might mere configurations of line, color and form affect us so significantly?

“When we describe art as ‘moving,’ just the word implies a change of state, and we can think of those changes at different levels,” explains Anjan Chatterjee, M.D., professor of neurology and a member of the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience and the Center for Neuroscience and Society at the University of Pennsylvania. “We can think of physiological changes — people, colloquially, will talk about experiencing chills or goosebumps when they have intense experiences. We can think of a change in our emotional or affective state, and that can go in any direction — it can be that we feel joyous, we feel pleasure, we feel enlightened, or we can feel disgusted, challenged, and so forth. And then there is also possibly a change in our cognitive state, which gets at an important question: Do we learn anything from art?”

The proposition that we can indeed learn from art is at the heart of a relatively new field known as aesthetic cognitivism, which purports that engagement with art advances knowledge and understanding. Indeed, descriptions often applied to art, such as “profound,” “thoughtful” or “eye-opening” suggest that art provides cognitive benefits, potentially changing how we view the world. To date, however, aesthetic cognitivism has been a philosophical argument, strengthened anecdotally by people’s personal accounts – gaining a transformative understanding of the horrors of war by viewing Picasso’s “Guernica,” for example, or gaining a new understanding of spiritual transcendence inside the Rothko Chapel in Houston.

“Most people can think of experiences where they felt transformed by some form of art,” Chatterjee notes. “While the idea that art teaches us something may be intuitively obvious to people who believe in its power, is that actually true? And if it’s true, how can we demonstrate that it’s true using scientific approaches? How do we generalize from personal opinion and anecdotes to place these strongly held intuitions on some kind of scientific platform?”

With funding from the Templeton Religion Trust, Dr. Chatterjee has embarked on a project to construct a research platform for putting aesthetic cognitivism to the test of science. His central hypothesis is that scientifically coming to terms with the impact of art may require precisely that: a curated lexicon of words that can serve as an instrument for collecting and analyzing quantifiable data.

His research begins with a deconstruction of the big, broad concepts and terms associated with aesthetic cognition. In an effort to bring granularity to its grandiosity, he’s posing provocative questions such as: What kinds of art are we talking about? What might be included under the broad category of understanding and knowledge? Do some kinds of art perhaps actively invite learning more than others? What constitutes a transformative experience? Can we create the viewing conditions in which people are open to learning?

Not unlike how a sommelier’s terminology – “fruit-forward,” “leathery,” “chewy,” for instance – add awareness and depth to wine-tasting experiences, Chatterjee considers words crucial to his investigation of the experience of art. And so the first phase of his research has been to collect words, creating “a list that is both relevant to aesthetic cognitivism, and would be useful for experimentation,” he says.

Compiling such a list proved to be an arduous process. First, Chatterjee assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts – an art historian, a theologian, a philosopher, a psychologist and another cognitive neuroscientist. Together, they comprised a brainstorming group whose task seemed deceptively simple at first: to compile a set of words that aptly describe art and its impacts, both emotional and cognitive. Although initially having such a wealth of inputs proved more unwieldy than anticipated, the diversity of viewpoints was crucial, Chatterjee emphasizes. “Especially in a topic that is so rich as aesthetic cognitivism, we wanted to make sure that we had people approaching this with a level of expertise from very different angles,” he notes.

Next, the team then went through a multi-stage iterative process to gain clarity and eliminate overlaps. The result of this careful winnowing was 124 terms that could describe different kinds of art — words such as “balanced,” “vivid,” “peaceful” and “banal” – and 69 terms that describe its impacts – “wonder,” “frightened,” “overwhelmed” and “joy,” for example.

From there, the list was crowdsourced to nearly 900 research participants, each assigned a term and one minute to come up with associated words. The researchers then looked for commonalities among this large data set. Using network science, they were able to create a visualization that accurately depicted what Chatterjee calls “the semantic space of aesthetic cognitivism,” with some terms closer, others more distant. Analyzing the resulting clusters and connections, they distilled a taxonomy of 11 fundamental terms, each describing a unique dimension of the impact that viewing art can provoke:

Taken together, these 11 terms provide a foundation for future research. This next phase will involve selecting actual works of art and then using the taxonomy for testing the impact of these specific works on research participants within defined research variables, such as the amount of time spent viewing the art, whether any information has been provided about it, and the viewing context (for example, in physical space versus on a computer screen).

As a neurologist, Chatterjee values words as an accessible gateway to the brain. “Language allows us to externalize our internal states and communicate that,” he explains. “Words, by virtue of externalizing an internal experience, puts it out there in a way that we can contend with.”

He’s unaware of any prior research that has applied scientific methodology to study aesthetic cognitivism. He intends to broadly share the results of this early research to encourage others. “One very concrete goal is that others who would like to investigate this have a readymade set of stimuli that they can use. Beyond that, I think if we can identify conditions in which people have these kinds of experiences of being moved, transformed or advancing their understanding, then those might be very useful for museums or religious institutions to create the environment in which this kind of impact is more likely,” he says.

Chatterjee also hopes his work can have relevance at an individual and deeply personal level by providing a set of words that make it possible for viewers to have richer experiences of art. “I think what language allows us to do is to make discriminations that otherwise might feel vague,” he says. “Some people make the argument that once you put this into words, you’ve lost the ineffable quality of things. I, personally, am not of that school. And so, one hope is than that having these terms when people are looking at art, just having a vocabulary, will enhance the experience. It’s about recognizing what it is you are experiencing because now you have this extraordinary human tool at your disposal, which is language.”