Accountability is usually understood in terms of holding someone accountable. But what if we, ourselves, embraced being accountable for the benefit of our relationships, families, and societies? What if accountability were seen as a human virtue? Could this benefit individuals, families, and the larger society? Dr. C. Stephen Evans of Baylor University is exploring accountability in exactly this way. Evans, and a diverse team of researchers, are exploring the possibility that accountability—embracing one’s own relational accountability to others—is a positive disposition, a virtue, which may strongly contribute to human flourishing.

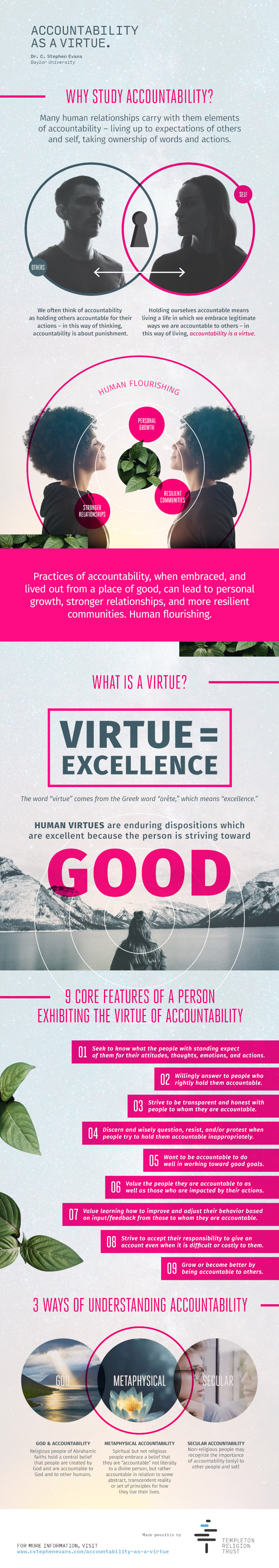

In Western cultures, we often talk about accountability in terms of demanding that public officials, big corporations, criminals, etc., be “held accountable” for their actions. What we often really mean is that we want them to be punished. But Dr. Evans and his team are asking the question, “What does it mean to be good at living accountably?” To fully explore this question, we must first examine what accountability means within society, different disciplines, and in relation to other virtues.

The broader study of virtues has gained a lot of ground in the past few decades as we have seen the importance of insights related to gratitude, compassion, humility, and forgiveness.

Like these other virtues, Dr. Evans and his team propose that accountability can support human flourishing, arguing that we live better lives when we embrace the legitimate ways we are accountable to others. To live well requires us to be morally responsible to each other and to God. If this is the case, then accountability would be considered a virtue – a form of excellence or striving toward good.

The word “virtue” comes from the Greek word “arête,” which means “excellence.”

Human virtues are enduring dispositions, which are excellent, either because they are good in and of themselves, or because they lead to other kinds of good – joy, ease and flourishing.

Although we can easily understand the importance of accountability in human relationships, people with different worldviews frame accountability differently.

Religious people of Abrahamic faiths hold a central belief that people are created by God to be accountable to God and accountable to one another.

Spiritual-but-not-religious people embrace a belief that they are accountable, not literally to a divine person, but rather in relation to an abstract, transcendent reality or set of principles that guide how they live their lives.

Non-religious people generally recognize the importance of accountability only to other people and to themselves.

The person to whom another is accountable must have the proper standing or authority to hold someone accountable. Standing can be very specific, defined by particular roles, such as a student to teacher, or an employee to supervisor. However, accountability is not merely directed “upward” to superiors. Students and, for example, have standing to hold teachers and accountable in some ways. Religious people may also see themselves as accountable to God for how they live.

In addition to having standing, the person to whom one is accountable should ideally have a concern for the well-being of the one who is accountable, rather than manipulating or coercing those accountable.

The project or shared task that is related to accountability must also be for a good end.

Working collaboratively with various disciplines, Dr. Evans’ project explores accountability through varied lenses—analyzing accountability in the context of various issues, ethics, and other forces.

Philosophy

By taking a philosophical approach, the study seeks greater understanding of how personal virtues are linked to social relationships, ethics, and autonomy.

Psychology

Research studies have focused on the development of scales to measure accountability and to assess relationships with other relational virtues such as gratitude and forgiveness. Experiments are testing the effect of mindsets that foster or impede accountability. Neuroscience research is also investigating the underpinnings of accountability through empathy and self-regulation, which are crucial for relational responsibility.

Sociology and Criminology

Within the disciplines of sociology, and criminology, this project seeks to more deeply understand how accountability may be linked to reconciliation, service to others, offender rehabilitation, identity transformation, and reducing crime. Embracing accountability as a virtue may help us to think more meaningfully about how to make prisons – and our criminal justice system as a whole – more restorative and less punitive.

Theology

Through theology, Dr. Torrance can examine the core religious concept of “living one’s life before God” in the context of a contemporary, highly secularized world.

Psychiatry

Via the tools of psychiatry, this study looks at how accountability relates to mental health and society’s treatment of people with mental illnesses.

Dr. Evans and his team will use society as a mirror to examine accountability, through multiple studies specifically in the fields of human flourishing, mental health, and prison reform.

“One of the areas we are exploring is that of criminal offenders – people who are incarcerated. We are studying the ways in which inmates participate in faith-based programs and how that involvement affects them in terms of virtuous behavior. We are creating a system of measurement that can help test whether accountability truly helps criminal offenders to change their behavior; whether being accountable to others, and to God, will impact identity transformation.”

– Byron R. Johnson, Distinguished Professor of the Social Sciences, Baylor University

C. Stephen Evans, “Accountability as a Virtue,” Logos Institute Podcast Part 1

C. Stephen Evans, “Accountability as a Virtue,” Logos Institute Podcast Part 2

What does it mean to live accountably so that accountability is a virtue?

Stephen Evans, Living Accountably: Accountability as a Virtue, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/living-accountably-9780192898104?cc=us&lang=en&

What is a theology of accountability to God?

Andrew B. Torrance, Accountability to God, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/accountability-to-god-9780198873938?cc=us&lang=en&

How do we understand and measure accountability as a virtue?

Witvliet, C. V. O., Jang, S. J., Johnson, B. R., Evans, C. S., Berry, J. W., Leman, J., Roberts, R. C., Peteet, J., Torrance, A., & Hayden, A. N. (2023). Accountability: Construct definition and measurement of a virtue vital to flourishing. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 18(5), 660-673. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2022.2109203

How do we understand and measure transcendent accountability?

Witvliet, C. V. O., Jang, S. J., Johnson, B. R., Evans, C. S., Berry, J. W., Torrance, A., Roberts, R. C., Peteet, J., Leman, J., & Bradshaw, M. (2024). Transcendent accountability: Construct and measurement of a virtue that connects religion, spirituality, and positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 19(2), 243-256. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2023.2170824

How does accountability as a virtue relate to medicine and health care?

Peteet, J. R., Witvliet, C. V. O., Glas, G., & Frush, B. W. (2023). Accountability as a virtue in medicine: From theory to practice. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine, 18, 1-6. https://peh-med.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13010-023-00129-5

How is accountability connected to flourishing, mental health, and autonomy?

Peteet, J. R., Witvliet, C.V.O., & Evans, C. S. (2022). Accountability as a key virtue in mental health and human flourishing. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 29, 49-60. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/850952

How does accountability relate to religion and reduced risk of aggression in the prison context?

Jang, S. J., Johnson, B. R., Witvliet, C. V. O., & Evans, C. S. (2023). Religion, accountability, and the risk of aggressive misconduct among prisoners: Preliminary evidence of restorative rehabilitation. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X231219213