Chaplains work across and bridge religious and spiritual divides.

Chaplains serve people not connected to traditional religious leaders.

What if chaplains were trained based on demand for their work in light of today’s changing religious context?

American religious life is changing fast. More people than ever describe themselves as unaffiliated with a religion, especially those under 30. Yet those unaffiliated continue to face unavoidable human challenges such as loss, sickness, life transitions, and death.

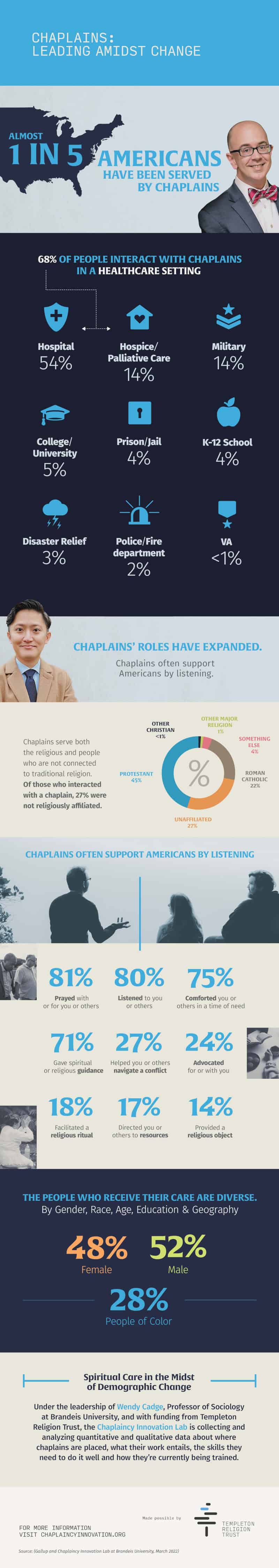

Chaplains (or “spiritual care providers”) have long served people in the midst of life’s challenges in places like hospitals, hospices, the military, prisons, and institutions of higher education. More of the people chaplains serve today are not connected to local religious leaders. Looking to the future, it is likely that chaplains will be the primary spiritual and religious leaders who care for growing numbers of people in the United States.

But are chaplains being prepared for this reality?

Is their training based on deep understanding of the needs of the people unaffiliated with religion?

Historically, chaplains have worked at the margins of society, rarely considered to be religious leaders in the way congregational clergy are. People may have been vaguely aware of the chaplain at their college, or maybe in a military unit. A chaplain may have come by when a loved one was hospitalized or in hospice. Most often, people’s exposure to chaplains has been in brief glimpses.

An important shift is underway, reports Wendy Cadge, Ph.D., a sociology professor at Brandeis University and a founder of the Chaplaincy Innovation Lab. “Until the recent pandemic chaplains were largely overlooked in public discourse,” Cadge reports. “But that changed with significant coverage in major outlets like The Atlantic, The New York Times, and other places. As fewer people are involved with local congregations, chaplains may be the only religious leaders they interact with in traditional settings like the military, prisons and healthcare organizations, and in new places like community organizations, social movements and a broader range of workplaces.” Chaplains don’t usually make the news and do “quiet work in some of life’s most sensitive moments,” Cadge believes.

In this quiet work, chaplains tackle the challenges of pluralism head-on. Going beyond mere tolerance, they’re engaging collaboratively and intimately across spiritual, religious and cultural differences – a mindset and a growing movement known as covenantal pluralism.

“The requirements of chaplains’ work have changed faster than educational programs can keep up with,” says Cadge. “Chaplains are trained in different ways to work in different sectors, siloed in ways that are best neither for the profession nor for the people they serve.”

Also, she adds, while the people who receive their care are diverse, chaplains are still overwhelmingly white, male and Christian. Most have graduate degrees in theology or the equivalent and some clinical training. But surprisingly, there’s no common standard for education, licensure or accreditation. Training curricula vary greatly, and truly interreligious courses or learning experiences tend to be the exception rather than the rule.

Under Cadge’s leadership and with funding from Templeton Religion Trust, the Chaplaincy Innovation Lab is engaged in a major, first-of-its-kind research effort. Working with an advisory committee of 28 stakeholders, including theological and clinical educators and social scientists, the team is collecting and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data about where and how the public interacts with chaplains, the skills chaplains need to do this work well, and how they are trained to do it.

The overall aim is to identify where there is demand for chaplains and their skills, how the current supply of chaplains meets these needs, and where there are gaps in meeting that demand – a first step toward igniting transformative change.

“We are convinced that educators cannot train chaplains well without information about where and how the work of chaplains is in demand, how they are enacting covenantal pluralism in those settings and what training best facilitates their key roles,” Cadge says.

“In some settings, this is demand for an actual chaplain. In other settings, the demand is for the skills of empathetic listening, improvisation, awareness of spiritual, religious and broad existential issues of meaning and purpose, and the knowledge and ability to comfort around death.

“In an age when formal religious identification is on the decline, it is tempting to suggest that the ‘benefits of religion’ have run their course and now are receding,” she continues. “We contend otherwise. Spirituality and religion are changing, not disappearing, and chaplains are changing in the process. Best preparing chaplains to lead in the current moment requires understanding how the public interacts with them and developing training programs based on that demand.”