What if we understood why certain music in certain places inspires us?

What if we realized how architecture shapes the way music moves and transforms us?

Could the evocation of awe be generated through acoustics?

Imagine hearing a funeral chant inside an ancient Egyptian tomb—every note hanging in the air just as it might have thousands of years ago—without ever leaving California.

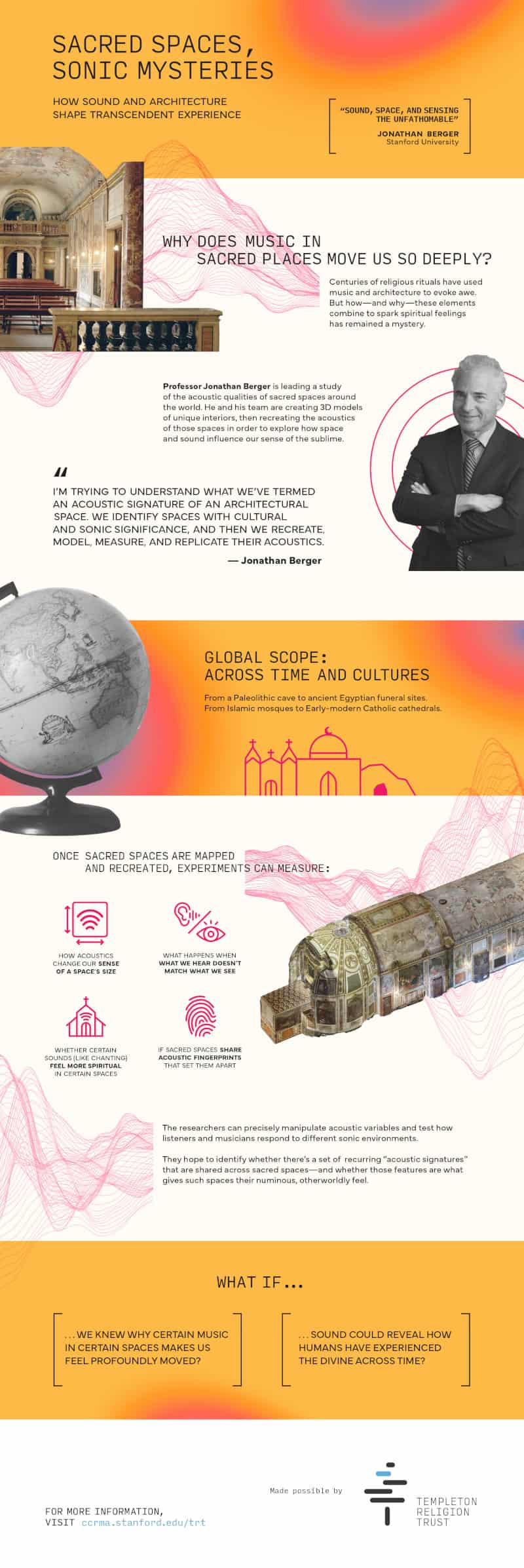

At Stanford University’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA), composer and professor Jonathan Berger is doing just that. His team is using cutting-edge technology to recreate the acoustic properties of sacred sites from around the world, like mosques, cathedrals, caves, and temples, and studying the effects these soundscapes have on human perception.

The initiative is titled Sound, Space, and Sensing the Unfathomable. Its goal is to investigate how the architecture and acoustics of sacred spaces evoke feelings of awe, reverence, and transcendence—and to do so with the rigor of scientific inquiry.

“I’m trying to understand what we’ve termed an acoustic signature of an architectural space,” Berger explains. “We identify spaces with cultural and sonic significance, and then we recreate, model, measure, and replicate their acoustics.”

This research is rooted in a widespread phenomenon: many people’s most profound spiritual experiences are linked to sound and space—whether it’s a choir echoing in a cathedral or a simple chant in a candlelit sanctuary. But until now, this powerful interplay between music and architecture has rarely been studied with the tools of empirical science.

The connection between spiritual feeling, sound, and space is as old as religion itself. Music and architecture have shaped religious ritual for millennia. And yet, most academic fields—archaeology, anthropology, even musicology—have traditionally emphasized the visual, the textual, or the ritualistic over the sonic. Sacred spaces were studied for their iconography and construction, not for how they sounded.

That’s starting to change. With emerging tools like spatial audio capture, digital modeling, and virtual acoustic manipulation, Berger and his team are creating new ways to explore how sound and space together create a sense of the sublime.

Their approach blends history, culture, technology, and psychology. By asking questions like, What makes a space feel sacred? The project probes the very limits of what can be measured.

The project’s roots lie in an often-overlooked Roman church: Chiesa di Sant’Aniceto, tucked inside the Palazzo Altemps. As Dr. Jonathan Berger studied its architecture and frescoes, he noticed something unusual. The space was adorned with angels holding scrolls of music and musicians mid-performance which, upon closer analysis, revealed a three-part canon: polyphonic harmony embedded within a single vocal line. It appeared to be an acoustic signature that indicated a deeper collaboration between sound and space.

This discovery added a new, ambitious line of research to Berger’s work: Can we determine whether some pieces of music were intentionally composed for specific architectural settings? If this is the case, our emotional responses to these pieces of sacred music in sacred spaces are the deliberate result of centuries of co-designed sound and structure.

As a lauded composer himself, Berger finds this not only plausible, but likely. Imagine composing a piece for a venue where a simple “hello” reverberates for three to five seconds. This phenomenon, known as harmonic decay, means each note lingers—enveloping the listener in resonance. In such a space, every musical phrase becomes an experience shaped, not just by sound, but by the architecture itself.

The project unfolds across three interconnected activities:

1. Mapping Sonically Sacred Sites

The research team is conducting a global ethnographic and cultural study of sacred spaces known for their acoustic properties. From cathedrals in Europe to mosques in Iran, burial chambers in Egypt, and ritual caves in the Andes, they’re building a catalogue of places where sound has spiritual weight.

2. Digitally Reconstructing Reverence

A diverse sampling of these sites will get a digital treatment at Stanford by methodically collecting test recordings, analyzing, and virtually reconstructing them. The team replicates these acoustics in physical labs and virtual simulations using a technology called CAVIAR (Chamber for Augmented Virtual and Interactive Audio Realities). Participants can hear how sound would behave in these spaces, without ever leaving the room and without wearing a headset.

3. Experimenting with Awe

At the heart of the project are four experiments designed to explore how sound, space, and perception interact to evoke feelings of awe, reverence, or transcendence. Berger’s team is using virtual reconstructions of sacred spaces, along with dynamic sound modeling, to study both the psychological and physiological effects of these environments.

The core hypothesis is that people may feel self-transcendent emotions when their senses receive conflicting signals about the space they’re in. For example, your eyes might tell you a room is small, but the sound—long echoes, complex reflections, lingering harmonics—makes your ears believe it’s vast. That mismatch between what you see and what you hear may confuse your brain in a way that opens up a feeling of ethereality or transcendence.

The experiments explore questions like:

By using CAVIAR and virtual reality systems, the researchers can precisely manipulate acoustic variables and test how listeners and musicians respond to different sonic environments. Ultimately, they hope to identify whether there’s a set of recurring “acoustic signatures” that are shared across sacred spaces—and whether those features are what gives such spaces their numinous, otherworldly feel.

At one level, this is a deeply technical project involving 3D rendering, reverberation modeling, and experimental design. But at its core, it’s about something simple and universal: the feeling that a space can be “holy,” not just because of what happens in it, but because of how it sounds.

This research can change how we design sacred architecture, how we preserve heritage sites, how we understand musical history, and even how we cultivate transcendent experiences today. Berger’s work sheds light on how performers and composers, across cultures and centuries, have intentionally shaped their work for particular acoustic environments.

More broadly, the project significantly advances conversations about how audio art might be quantitatively understood as a way humans learn and grow. Berger envisions “a new domain of study that looks broadly and deeply at the interplay between sound and space, and at what this means in the history of art, culture, and humanity.”

Through ancient tombs and virtual cathedrals, measuring hand claps and harmonic decay, Berger and his team are opening up a new frontier in how we understand reverence, architecture, and sound. They are not just restoring the echoes of the past—they are revealing how reverence and awe might be embedded in sonic experience.

In doing so, Sound, Space, and Sensing the Unfathomable bridges the gaps between art and science, and invites us all to listen a little more closely in the special spaces we sometimes find ourselves in, that seem to speak to us in a language without words.