Hurricanes. Tornadoes. Addictions. Illnesses. Poverty. Homelessness. Prejudice. Oppression. Wars.

There are so many cases and causes of human suffering in our world today. And we’re exposed to all this suffering more than ever.

Technology brings it instantly into nearly every room of our homes. Almost every day we see victims of distant disasters up close. We hear the distress in their voices even when we can’t understand their words. What’s more, wherever we live or travel, we’re apt to be confronted by people with handwritten cardboard signs: “Homeless. Please Help.” “Hungry. Please Help.”

More exposure to suffering means more moments of choice: respond or not? Most of us likely think that compassion is a morally good thing. But putting it into practice is often less clearcut and automatic.

“Compassion may not be the natural response that everyone feels when faced with suffering,” says Patty Van Cappellen, Ph.D., an assistant research professor at Duke University. “As critical as it is, compassion doesn’t always flow easily. For various reasons, we regulate our responses.”

For instance, compassion takes up our time. Often it involves our money. Sometimes the need is so great that we decide it’s too much to take in and take on. Instead, we shut down emotionally and turn away. Or we decide that anything we might do would be just a drop in the bucket, so why bother? Or we get hung up on judging and blaming, pointing a finger instead of extending a helping hand.

With so many costs and reasons to avoid compassion, can it survive much less thrive in today’s complex and needy world? If so, how? What might make a meaningful difference in people’s ability to be compassionate?

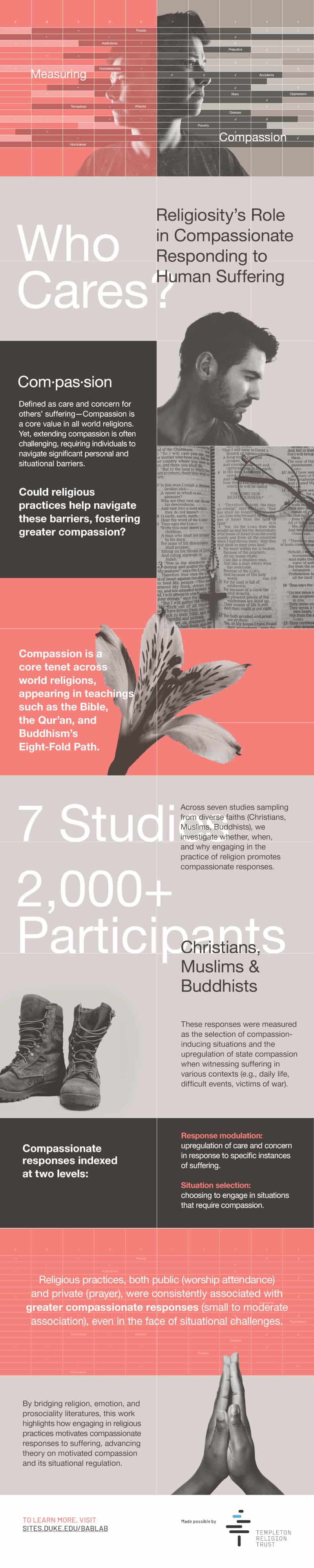

A social psychologist who studies spiritual practices and beliefs, Van Cappellen points out that compassion is at the core of almost every religion.

“Studies have concluded that each of the major religious traditions — Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, and Islam — have a significant commonality in their systems of belief: compassion,” she notes.

However, surprisingly, religion has been mostly missing from psychologists’ research into compassion. Does religion make people more compassionate, or less? So far, there’s little solid evidence linking the two. Some previous studies have shown that religious people will say they’re compassionate, and their friends will agree. But does this self- and peer-reporting translate into observable compassionate responses?

With a grant from Templeton Religion Trust, Van Cappellen is conducting a project to better understand religious people’s capacity for compassion.

“What can we learn from the ways through which religion is lived in faith communities to improve our understanding of the factors that promote compassion?” she asks. “In this project, I consider compassion as more than simply understanding what someone else is feeling or just the cognitive part of it. I am especially interested in the emotional aspect of compassion — our capacity to feel someone else’s pain and to be concerned about them.”

“Empathy is a perspective, and compassion goes beyond that,” she says, “Compassion is our cognitive and emotional capacity to understand and feel someone else’s pain and to be concerned about them. This concern about how others feel is critical to motivating actual helping behaviors. Compassion is critical because, more than merely a feeling, it’s a precursor to doing.”

To date, Van Cappellen has looked at new data among 1,700 participants across four studies plus archival data from 3,000+ participants across three studies.

The project includes more than a dozen distinct tests to collect data on a range of variables. For instance, one test involves more than 400 participants: some who identify as religious as well as some who don’t. They’re shown photos of suffering people and given the option to either:

1 | Describe the person factually (age, demographic, surroundings, etc.)

or

2 | Describe how the person may be feeling (sad, alone, desperate, etc.).

Will religious participants choose the compassionate response – i.e., choose to describe feelings versus facts — more often than nonreligious participants? And, if they do, are they more compassionate? If so, why might that be?

Do participants who are primed to think about their beliefs in God show more compassion than people who are simply asked to describe how they get to their grocery store? How do their responses to the photos compare to participants who are instead asked to start by describing how they get to their grocery store? Will engaging in a group prayer for suffering people at the beginning of a study measurably affect how participants respond to photos of people suffering? Will those who frequently engage in religious practices such as worship, meditation, and prayer respond differently to the photos than those who don’t?

Through tests such as these, Van Cappellen hopes to gain a better understanding of:

The first phase of this research is now complete. Van Cappellen reports the results show a significant influence of religiosity on whether people choose a compassionate response when shown images of suffering people. At the same time, across all studies, the results show a moderate association between individual differences in the degree of a person’s religiosity and how much they feel for and care about people who suffer. They also report less perceived distance to the victims and a greater sense that it is their responsibility to help.

Future tests aim to test whether religion 1) provides normative, affective, and social motivations for compassion, and 2) affects perceptions of the emotional and cognitive costs of compassion.

The findings may begin to shed light on these important unknowns, possibly unlocking new insights into compassion and leading toward more targeted ways to encourage it in our world today.