Can religion truly act as a moral compass, guiding behavior across different situations?

Are religious people more consistent in their moral choices than non-religious people?

Can science measure the impact of religious belief on real-world behavior?

As a visitor to Istanbul, you might find yourself following your traditional Turkish breakfast—sesame bread and coffee—with a tour of the Hagia Sophia. This historic landmark has carried the identity of church, mosque, and museum, encapsulating centuries of cultural forces battling for influence. But how do these forces shape the daily life of the person who just served your coffee?

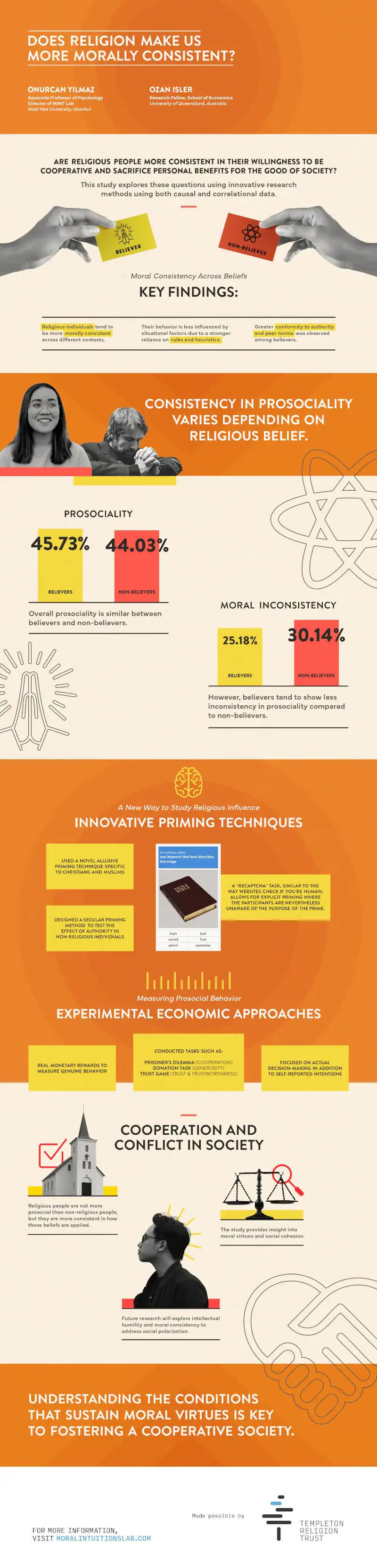

“In this project, we try to understand whether religious belief serves as a universal moral compass,” cognitive scientist Onurcan Yilmaz explains. The influence of religious belief has been sometimes underestimated in academia, leaving it understudied. Existing research methods have also proven weak in many ways. This team is making waves, both through the insights they’re uncovering and the methods they’re using, to understand the connections between religion and real-world behavior.

While Yilmaz and co-project leader, Ozan Islar (a behavioral economist), are pursuing hard data about whether religion makes individuals more morally consistent, they are keeping a larger purpose in mind. On a social level, they hope these insights can lead to more cohesive communities. Islar and Yilmaz believe deeper understanding can be leveraged for the common good. The new methods introduced in this study will provide some of the most reliable information to date.

What does it mean to see religion as a “universal moral compass”? Religions have overtly tried to create positive social norms throughout human history. In the Abrahamic religions, the Ten Commandments serve as a quintessential example of moral principles meant to be applied universally—across different situations and contexts. These religions have the added theological motivator of an omniscient God watching over you. Islar and Yilmaz’s team see this as helpful in establishing a connection between religious beliefs and behavior.

The home of this research team has a special significance and advantage for examining this connection. Their Moral Intuitions Lab (MINT) is at Kadir Has University in Istanbul, just a few miles from Hagia Sophia. “[Istanbul] made its transition to secularism almost 100 years ago,” Yilmaz explains, although, “religious authorities are still in power. This makes Istanbul a perfect place to study both secular and religious influences on people.”

Bringing real-world behavior to the lab can get complicated. For example, when asked how much money they might hypothetically donate, people tend to idealize their behavior. But when participants are given real money to allocate, they can’t rely on idealized self-reports. This approach avoids bias and provides real-world applicability.

Isler and Yilmaz chose donation tasks and three other games, all with real financial stakes, to gather robust data on moral domains like generosity, cooperation, and trust. To measure consistency, they designed the study to span a full year.

Correlating behavior with religion is accomplished through priming techniques. In traditional priming, participants are asked to reflect on religious concepts before completing a questionnaire or task. However, this can skew the accuracy of the results, creating the “demand effect.” This occurs when participants pick up on clues about the study’s topic and alter their behavior to comply with (or defy) perceived expectations.

In this study, researchers created a “supraliminal” priming method, in which participants are primed more subtly. One such technique involved giving participants a foreground task with religious imagery placed in the background, unrelated to the task at hand. For example, while a Christian participant completed a security CAPTCHA, a page of the Bible served as the background image; a Muslim participant saw a picture of a mosque or a page from the Qur’an. Participants’ behavior is more likely to reflect authentic decision-making, influenced by the primes, rather than their interpretation of what the study is about.

The MINT Lab hypothesized that religious people would show more consistency in their moral behavior across time and contexts, and their findings support this. Religious believers often rely on faith principles as shortcuts for decision-making, bypassing the need to consider variables and applying principles they value from their faith. This moral consistency fosters trust and reliability in communities.

Non-religious individuals, by contrast, are more likely to evaluate each situation differently (e.g., who’s involved, personal experiences, consequences). This tendency leads to less moral consistency but greater adaptability in complex scenarios.

That said, there was no notable difference in the overall level of prosocial behavior between believers and non-believers. Non-believers were just as cooperative, generous, or trustworthy as religious folks, but their prosocial behavior varies more between situations. This demonstrates an important link between religion and moral behavior and has implications for understanding dynamics between social groups.

This research leads to more questions, especially given the dark side of religion. Religious systems can foster cooperation and social cohesion, but they can also aggravate conflict, polarization, and extremism. By understanding the influence of religious and non-religious belief systems on behavior, the MINT Lab team hopes to create opportunities for connection across differences.

The findings and the new methods utilized in this study set the stage for future discoveries. There’s further work to be done, not just in comparing believers and non-believers, but in exploring nuances between different religious groups. There are also questions about how believers’ rule-following tendencies interact with the virtue of intellectual humility—the extent to which someone can be open to new perspectives and admit when they are wrong.

Just as important as identifying differences is identifying similarities between groups. Once named, these commonalities could be used to design strategies for cultivating cooperation and mutual respect. All these factors will have a real impact on how well our society can thrive in the future.

Much like the Hagia Sophia, with its layered history of both power struggle and coexistence, this research holds the dual nature of religion: a force that can unite communities through shared moral frameworks, yet also divide through rigid boundaries. The MINT Lab’s study illuminates how religious belief serves as a moral compass, fostering consistency and trust. It also challenges us to understand the subtler dynamics at play in secular frameworks and the common ground between believers and non-believers.

As Isler puts it, “Our findings open up new venues for future research in connecting religious belief systems with secular belief systems in how they allow cooperation and successful civilizations.” This work invites us to approach the complexities of belief with curiosity, recognizing both the promises and pitfalls of religion’s influence on morality.