What if we understood more about our own views of the world?

What if we understood more about others’ views?

Have you ever noticed this? People can be in the same place at the same time …. and yet have vastly different experiences.

Riding a city bus, for example.

Some people appear relaxed. They’re taking in the sights, maybe listening to music, pecking away on their devices or exchanging a few words with someone nearby. Others, however, look tense, their eyes furtively darting or focused downward on the floor, arms crossed protectively, seemingly on full alert.

They’re all sharing the same space but responding to it very differently. Is it simply a matter of different personalities? Or maybe some are just having a bad day?

Or could another large and pervasive force be at work?

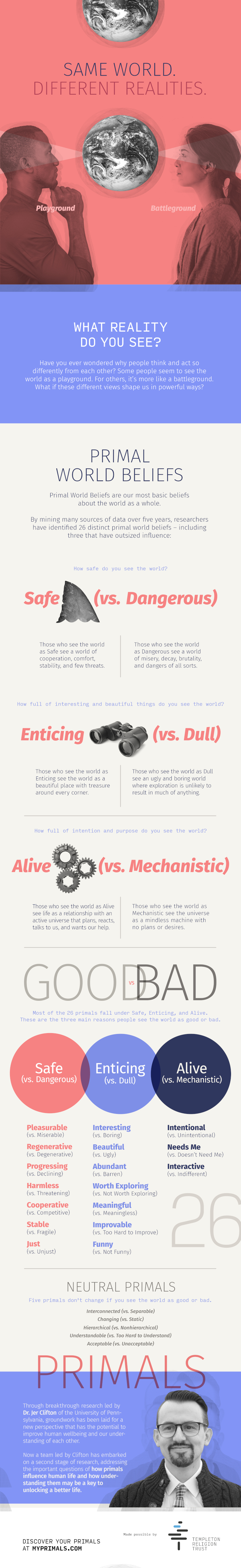

Jer Clifton, Ph.D., director of the Primals Project at the University of Pennsylvania, contends that humans have different fundamental beliefs about the world we all inhabit. And those beliefs can be a principal cause of why we think and behave very differently.

“You and I could be sitting next to each other. We could be from the same town. We could even be siblings who grew up with the same parents,” he says. “And yet we could dramatically disagree about the sort of world this is.”

Since 2014, with support from Templeton Religion Trust, Clifton has been leading a breakthrough research effort to uncover and classify people’s fundamental world beliefs. He’s labeled these beliefs “Primals” because they are so fundamental, potentially influencing virtually everything we do.

“We don’t form perceptions based on what’s objectively true of the world. Instead, our senses give us bits and pieces. And our brains are figuring out as quickly as possible how to fit those pieces together in a way that makes sense. So a general belief about the world as a whole is potentially a critical part of deciding what makes sense to us — what seems likely, what seems real.”

Clifton’s research began with an exhaustive effort to produce a comprehensive data inventory for analysis. The work encompassed 10 distinct inquiries and 70 investigators. “We tried to cast a wide net,” he understates.

The team analyzed the 840 most-used adjectives in modern American English, drawn from a representative 190-million-word database. They mined a database of more than 2 billion tweets to extract approximately 80,000 that expressed a view of the world. They conducted a dozen focus groups involving participants representing the world’s major religions – Islam, Christianity, Hinduism and Buddhism. Five scholars gathered relevant work in six disciplines—psychology, philosophy, art history, comparative religion, anthropology and political science—to compile a 415-page compendium. And 10 American experts, including noted evolutionary biologist Dr. David Sloan Wilson of Binghamton University and Stanford belief psychologist Dr. Carol Dweck, met for three days at the University of Pennsylvania to compare insights. Top Chinese scholars did the same at Tsinghua University.

From this vast reservoir of data and relying on methods of statistical factor analysis, Clifton’s team created more than 200 questions about the character of the world that they then administered to thousands of people. Multiple follow-up rounds involved bigger and bigger sample groups.

Consistently, the researchers saw the same results.

From this massive inventory of data, Clifton reports four key discoveries:

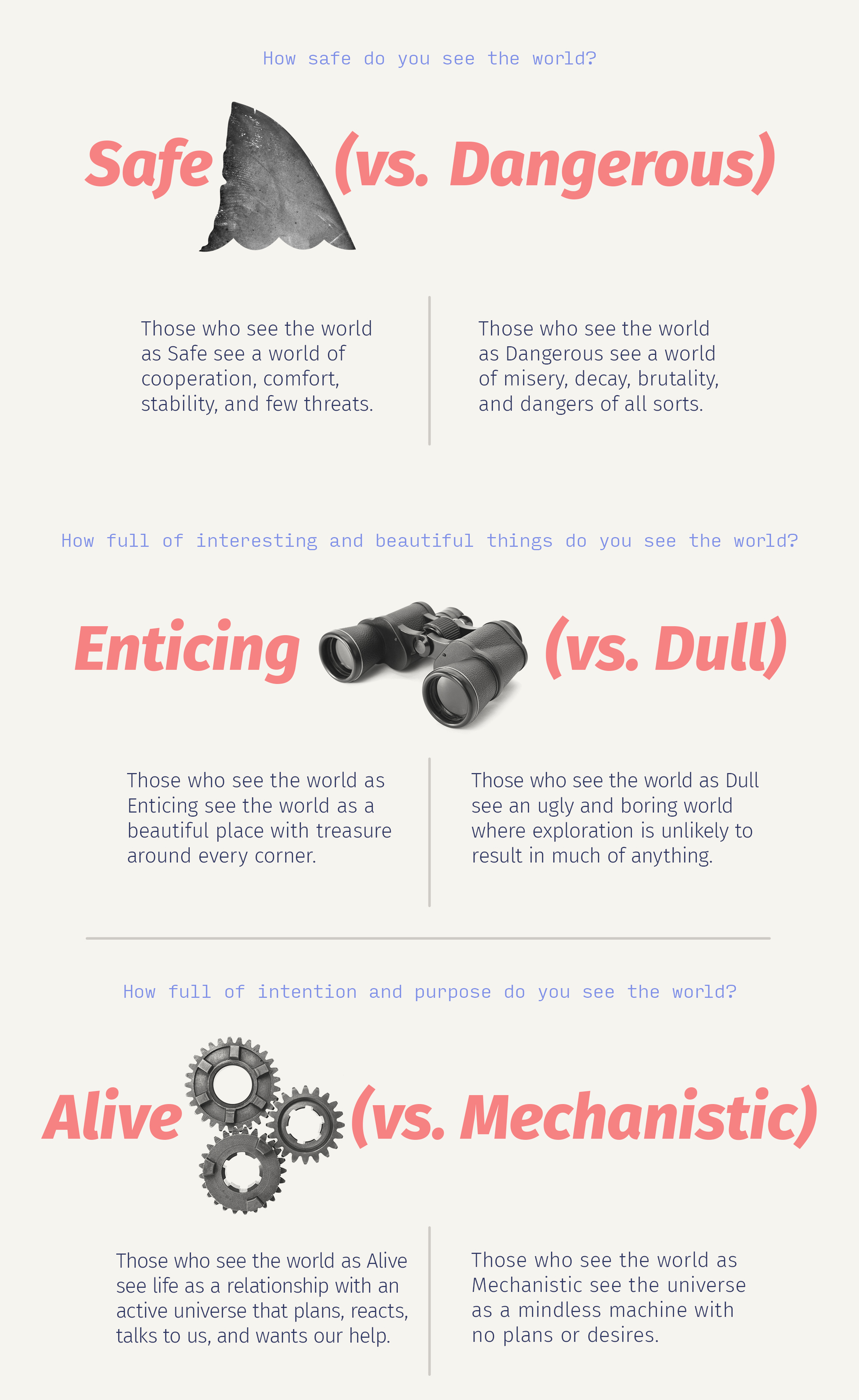

Moreover, the researchers found that each primal belief has its polar opposite, like the two ends of a teeter-totter. People are oriented – some more and some less – toward one end of the continuum or the other.

Most of these 26 beliefs cluster into three main beliefs:

Now that Primals have been identified and an efficient tool has been created to measure them, Clifton’s team has shifted to the next stage of research: digging deeper. This involves investigating how Primals are formed and maintained, how they influence personalities and behaviors. Plus how understanding them — and, in some cases, modifying them — might lead to a more positive, productive way of living.

Instead of functioning as mirrors that reflect what our lives have been, the evidence suggests that Primals are more like lenses we use to interpret our lives. “Lots of people with amazing lives see the world as a terrible place. And lots of people with objectively really bad lives see the world as wondrous,” Clifton reports.

Like whatever lens a photographer puts on a camera – zoom, telephoto or fisheye, for instance — Primals change the image of the world that we perceive. So much depends on what lens we choose.

So far, the Primals research and findings have been mostly correlational. “We don’t know causes yet. We have a good idea about where these beliefs don’t come from. But so far we have very little idea about where they do come from,” Clifton says.

Although conclusive evidence may be years away, preliminary analyses — looking at an array of outcomes ranging from depression to job promotions among more than 4,500 study participants – suggest that people with negative world beliefs are, on average, worse off. They experience poorer health, more depression and suicide attempts, and much less life satisfaction and well-being.

For Clifton and his team, despite all they’ve learned so far, a massive amount of investigation into the origins and impacts of Primals remains to be done. More immediately, however, they hope their work will raise awareness that humans profoundly disagree on the sort of world this is and, although we may not realize it, these beliefs can affect our behaviors.

More research is needed to explore a wide variety of applications of this new storehouse of knowledge, including the possibility of gaining insight into such personal questions as: What primal world beliefs should we teach our kids? How do my primal world beliefs affect my marriage? What about my relationships with family and friends? Ideally, the work of Clifton and his team could help people see reality with new eyes. As a result, more of us may be able to lead more productive and satisfying lives while also gaining the capacity to understand others.

A free online survey provides an easy way to discover your primal beliefs and reflect on how they may affect what you do and think. Choose from three versions. The longest takes just about 15 minutes, the shortest about 2.

Visit myprimals.com