What if the boundaries between science, technology, and religion aren’t as solid as we may think?

What if popular assumptions that science drives secularization aren’t true?

What if understanding environmentalism could lead to deeper spiritual meaning?

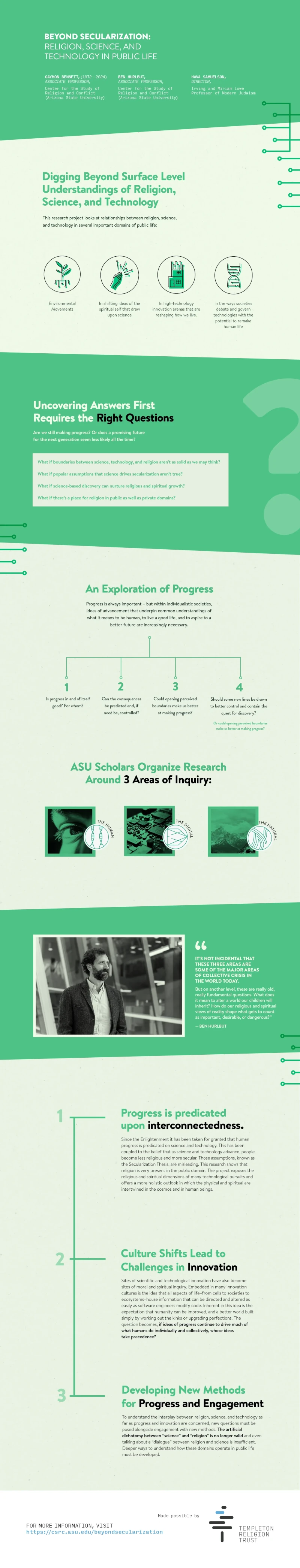

Are we still making progress? Or does a promising future for the next generation seem less likely all the time?

These are big questions being asked often these days.

From gene editing to generative AI. From medicines to cure aging to the rapid rise of artificial intelligence. From the trauma of Covid to the cinematic retelling of Oppenheimer’s development of the atom bomb.

Deeply tangled around the heart of developments such as these is a growing uneasiness about where science’s inventions may be taking us. At the same time, in places like Silicon Valley, innovators are imagining a technological future that can bring redemption to our lives in new forms.

Is scientific progress in and of itself good? Is advancement in science and technology synonymous with progress? What questions should be asked in the process? Can the consequences of technological innovation really be predicted and, if need be, controlled? How and when do ethical, moral, and religious considerations come in? How and when do they get left out or excluded? Does achieving true progress require drawing new lines and developing better ways of thinking about the meanings of the futures we face?

A team of scholars at Arizona State University led by Ben Hurlbut, a specialist in science and technology studies, Hava Tirosh-Samuelson, an historian of religion and environmentalism, and Gaymon Bennett, an anthropologist of religion, science and technology, are convinced that issues like these are critically important for our time. Supported by Templeton Religion Trust, they together designed and are now leading a boundary-pushing social research project. Its aim is to explore ideas of progress that underpin our common understanding of what it means to be human, to live a good life, and to aspire to a better future—ideas which are culturally powerful but are seldom questioned.

By assembling a distinctly interdisciplinary group of faculty, post-docs, and graduate students, the ASU team is purposefully crossing scholarly boundaries between history, science and technology studies, religious studies, sociology, and anthropology. As Hurlbut points out, traditionally, these academic disciplines have been centered on distinct sets of questions and frameworks. Hurlbut is confident that joining them in a common endeavor can result in a transformative new model of dialogue, research, and application.

“Our basic conviction is that to understand the interplay between religion, science, and technology, we need to pose new questions and engage new methods,” he explains. “The artificial dichotomy between science and religion is no longer valid. Even talking about a dialogue between science and religion is insufficient. We need to develop deeper ways to understand how these domains operate in public life.”

Working as a collaborative laboratory and using qualitative methods drawn from the social sciences and humanities, the ASU team is focusing their research on three key areas:

As scientists, ethicists, and the public seek to make sense of the significance of advancing biotechnologies, questions of human identity, integrity, and dignity have become central. Sites of scientific and technological innovation have also become sites of moral and spiritual inquiry.

This research area explores how conceptions of the right uses of science and technology – developments that could alter our ideas of being human — are taking shape in arenas of research, innovation, and governance, and how these in turn reflect underlying assumptions about progress, the inevitability of technological developments, and their meaning for ways of understanding what it means to be human.

Embedded in many innovation cultures is the idea that all aspects of life can be directed and altered as easily as software engineers modify code. This research area explores the complex spiritual visions that today’s tech enclaves emerge from—and give rise to—visions in which technological innovation is the key to material abundance, political freedom, and the evolution of human consciousness.

How we think about nature and ourselves are central concerns of both science and religion. These ideas frame a moral relationship, affecting how we relate to the natural world and to each other. They even shape how we think we know— whether by intuition, reasoning, measured studies, mystical experiences, or something else— as well as what we think that knowledge is good for.

Through case studies, fieldwork, and interpretative analysis, this research area explores how the material world and the self are being reconceptualized and reinvigorated by eco-theologians, environmental activists, and spiritual entrepreneurs.

“Our aim is not to discover merely what people believe about these phenomena,” Hurlbut explains. “Rather, it is to examine how social activities—such as the debate about what gene editing means for human identity and dignity—produce, enforce, reflect, or sustain particular ways of thinking and talking about science, technology, secularity, religion, and progress in public life. We’re also examining how these ways of talking in turn shape social life, particularly by informing institutions with deep cultural reach like law, norms, forms of public authority, and discourses. This is important because ideas about what is the right relationships between science and religion for achieving progress get socially enacted and culturally governed.”

It’s not incidental that these three areas are some of the major areas of collective crisis in the world today. “But on another level,” Hurlbut points out, “these are really old, really fundamental questions. What does it mean to alter a world our children will inherit? How do our religious and spiritual views of reality shape what gets to count as important, desirable, or dangerous? Our lives are saturated with science and technology. It’s fundamentally changing how we relate to ourselves, our bodies, our planet, our food, our lovers, and our sense of a higher reality. All these areas cut across time, place, culture, and tradition, and they’re some of the most pressing issues that humanity is facing today.”

As such, they mandate a broadened arena for investigation, discussion, understanding, participation, and decision-making. By catalyzing new scholarly work, inspiring conversations among the public and among thought leaders, and providing training for future scholars, the ASU project is an important, just-in-time effort that has potential to change how we think about progress and the human future.